A journey of resistance

became the new face of the antiwar movement in early 2004 when he applied for a discharge from the Army as a conscientious objector. After serving for nearly nine years, he announced that he would defy an order to redeploy to Iraq--making him the first known veteran of that war to refuse to fight, citing moral concerns about the war and occupation.

Despite widespread public support and an all-star legal team, he was eventually convicted of desertion by a military court and sentenced to a year in prison; he was released after serving almost nine months.

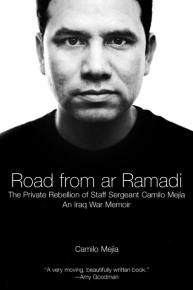

Mejía told his own story in the book Road from Ar Ramadi, now published in an updated paperback edition from Haymarket Books. Here, we print the new introduce to this edition.

This fall, Mejía will join other authors on the Resisting Empire speaking tour, organized by Haymarket Books.

THE IDEA behind writing Road from ar Ramadi first occurred to me while I was living underground in New York City. At the time, I was contemplating the various consequences that could befall me for being critical of the U.S. occupation of Iraq. I knew that if I spoke publicly about why I had refused to return to my unit in Iraq, the U.S. Army would want to silence me. Although I had always wanted to be an author, writing this memoir was separate from that aspiration. Writing Road from ar Ramadi was a way to ensure I would not be silenced even if I ended up behind bars.

The reasons I wrote the manuscript have turned out to be more complex than simply wanting to get out my version of the story. The Argentinean writer Ernesto Sábato once wrote in one of his novels that he could not be held responsible for the actions of his characters. I think the same is true for memoirs and for other nonfiction writing. There are driving forces behind everything we do that can be found outside of our intentions. In the case of this memoir, the original purpose was to tell my version of the story because I did not know if I was going to be in jail for a long time. But I did not start working on the manuscript until after I was released from military prison. The need to make my voice heard from behind bars was no longer a consideration when I began the actual work. I now realize that writing the memoir had a different purpose in my life: it was something I had to do in order to begin my healing process.

Shortly after my return from Iraq, my stepsister asked me if I had been in any combat missions and if I had fired my weapon. I began to tell her about the time my squad was ambushed. For the first time, my voice broke as I described the event. I had spoken about the incident after it happened with members of my platoon in Iraq, but back then, we were too concerned about what would happen next to truly discuss our feelings. Keeping our guard high always meant that the horrible things we experienced in the war were thrown in a trunk of suppressed memories. These emotions and memories only resurfaced after I started working on the manuscript, over a year after my public surrender to the military and almost four months after getting out of jail. Most of the year it took me to write the memoir was actually spent staring at a blank computer screen, remembering, reliving, and coming face to face with painful experiences for the very first time since I left Iraq.

Dealing with the memory blanks I had and still have made writing difficult, but perhaps even harder was understanding why my memory failed me when I tried to revisit very difficult moments. It was never the whole incident but bits of information that were missing from my recollection of events: the age, face, and emotional expression of a child who had just witnessed the brutal killing of his father or the face of a young man who was gunned down for throwing a grenade at our building. It is mostly the faces of people who carry the pain we inflicted in their lives that are hard to remember. Those faces may be missing, but the pain they carried we now carry with us.

Negotiating those memory gaps meant that I had to initiate a sincere dialogue between the part of me that had gone through the experience of war and the part of me that wanted to write about it. That dialogue became problematic when I tried to provide answers to the many haunting questions that, time after time, remained unanswered.

It is clear to me now that there are limits to what we can share, not only with other people, but also with ourselves. Those missing memories are part of an experience far too overwhelming to be fully contained, understood, or explained. Their missing is not a form of absence, but rather a statement of how war can profoundly change the human soul, removing memories and banishing them into dark and inaccessible corners of the subconscious, while pain, guilt, and despair occupy center stage in our daily lives. After I reached an agreement with myself to leave out the missing details, I was able to write, and I found the process less painful and more therapeutic. But the joy of finishing the manuscript was short-lived, to say the least. The product of a year's struggle to reclaim memories buried beneath layers of fear in order to bring them to light was now to be cut down during another agonizing process--editing, which would last six months. By the time my editor and I finished working on the original manuscript, close to a third of the manuscript was gone. Although I understood the logic behind keeping the book concise, I could not help feeling like a parent at a maternity ward who is told by the doctor that for the baby to survive all its extremities had to be amputated.

The book was officially published six months after we were done with the editing, a year after I finished writing the manuscript. At that time, the writer's vanity took a hold of me. I started to obsessively look for reviews and sales rankings on the Internet. What had begun as the need to express myself in the face of imposed silence, punishment for my rebellion, and which had later become a process of self-exploration and healing, was now reduced to a selfish need for literary recognition.

Things began to change when I went on a pre-release book tour in Southern California, sponsored by the San Francisco chapter of Veterans For Peace (VFP). In two weeks of speeches and readings, we did not visit a single bookstore. We concentrated on community centers, churches, and alternative high schools where troubled and disadvantaged youth went after traditional schools gave up on them. These students, who lived their lives in the margins of society and who were the prime target of military recruiters, could not afford to buy the memoir, but my conscience could not afford to leave them empty-handed. We started donating the book to the school libraries and letting students buy it at cost, or for whatever money they had, which many times meant giving it away for free.

I slowly began to realize that the success of Road from ar Ramadi was not to be found in literary magazines or sales rankings, but at the community level, where grassroots activists battle against a system that refuses to place human interest above profit and that feeds on poverty and disadvantage to fill the ranks of its military.

Not too long ago, I received a phone call from a group of students from a Catholic high school in California. They had read about me in one of their classes and wanted to interview me for an assignment. They had been really touched by my actions and thought I was a prophet. By any stretch of the imagination I remain sure that I am no prophet, I told them, but knowing how my actions and words are having a positive impact on young people is a reward that cannot be matched materially.

The memoir before you has been transformed yet again--this time into a tool of activism, a sort of chisel I hope will contribute to the carving of a new world, beginning by working on ending the occupation of Iraq through organizing around military resistance. A few words about that resistance would be appropriate.

WHEN I first refused to return to Iraq in October of 2003, no combat veterans had taken a public stance against the war. Air Force Capt. Steven Potts and Marine reservist Stephen Funk had been the only two public resisters, but their resistance occurred prior to the invasion, and their cases received little to no attention from the media. At that time, when the nation was rallying behind the president and the antiwar movement was just beginning to gain strength, resisting the war from within the military was a lonely path to walk.

The political climate has significantly changed since October of 2003, when the news was that morale among the troops in Iraq was high, and when only 22 service members had failed to report back for duty after their mid-deployment furloughs. Only five months later, the number of GIs who didn't report back to their units had grown to 500. When I got out of military jail in February of 2005, after serving nine months on a desertion charge, the same number was 5,500.

Today's military, developing from blind and unwavering obedience to entire units refusing to go out on combat missions, has come a long way in resisting the war. But those of us organizing in the military cannot take full credit for that change, nor can civilian organizers. It will take a deeper analysis of what is happening inside the military, and outside the antiwar movement, to understand why service members are saying "no" to their superiors.

The military's attempt to repress dissent within the ranks has mostly concentrated on suppressing public criticism of the war, and it has remained strong since I spoke out. A month after my court martial, Army Sgt. Abdullah Webster, a U.S. Muslim, was sentenced to 14 months of incarceration for refusing to deploy to Iraq. Webster was followed by Navy Petty Officer Third Class Pablo Paredes, who refused to board his amphibious assault ship, Bonhomme Richard, as it sailed off to transport marines to the Middle East. Paredes was sentenced to three months of restriction and two months of hard labor. Other high-profile cases include that of Sgt. Kevin Benderman (fifteen months), Specialist Agustín Aguayo (eight months) and Lt. Ehren Watada, the first commissioned officer to publicly refuse orders. Lt. Watada called the war illegitimate and cited the Geneva Convention and UN Charter as the legal basis of his defense. Though his court martial was dismissed, the military is still pursuing a retrial.

While most of the prominent cases of GI resistance have revolved around political opposition to the occupation of Iraq, it would be a mistake to generalize the current military resistance as purely political, or even as purely antiwar. As early as July of 2003, a platoon from my infantry unit engaged in negotiations with our company commander to modify an ongoing mission after unsound practices cost that platoon four casualties and a vehicle, and led to the killing of an innocent Iraqi civilian. In October of the following year, an army reserve platoon of truck drivers made the news after 17 of its members refused to go on a supply mission that they called "suicidal." And in 2007, as reported by Democracy Now! in December, after losing five of its members to an improvised explosive device (IED) attack, a U.S. Army infantry platoon refused to go back out after the incident, citing fear of committing a massacre in retaliation for the loss of their fellow soldiers.

We also have the resistance of Specialist Katherine Jashinski who, in November of 2005, refused deployment orders to Afghanistan, declaring herself a conscientious objector, but avoiding being politically critical of any war. In 2006, Army Specialist Suzanne Swift refused a second deployment to Iraq with the same supervisors who had forced her into a sexual relationship in exchange for not sending her on senseless, suicidal missions, a practice known as "command rape." Army Reserve Col. Janis Karpinski, during a public tribunal on war crimes committed by the Bush administration, said that female soldiers were dying of dehydration in Iraq. The reason was that, in those extreme heat conditions, they would purposely stop drinking water after noon so they wouldn't have to urinate at night, thus avoiding the risk of being raped by fellow soldiers on their way to the latrine. In the case of units refusing to go out on missions, as well--as in the cases of Jashinski and Swift--military resistance originated not from a profound political analysis of the invasion and occupation of Iraq but from a more primal, human refusal to participate in one's own detriment, be it physical or spiritual.

The supply and infantry units that refused their missions are not necessarily antiwar. Just as in the case of the two female resisters, these are people who are simply saying, "I refuse to kill or be killed." And, "I refuse to be raped." An effective antiwar movement should recognize the diverse nature of military resistance in order to work with these individuals and involve them.

When people join the U.S. military, in the overwhelming majority of the cases to escape poverty, the understanding is that the possibility of war will only come after all other venues to peaceful resolution have been exhausted. There is trust in the government to act within the parameters of national and international law and in the people of the United States to hold its government responsible for any misuse of the armed forces. War, we are told before signing the enlistment document, will only be our last recourse, and will only occur to protect our country--or perhaps to advance freedom and democracy.

It is no wonder then that servicemen and servicewomen have a hard time seeing the bigger picture, understanding that the senseless missions, that the risk of being raped by their peers, that the fear of taking human life without a noble reason, are all directly tied to the policies behind military action. The propagation of an inhuman, cruel, misogynist, and racist subculture in the military (to a significant degree, a reflection of the larger culture) is necessary to create the conditions in which a land and its people can be denied their sovereignty through military force. Military resisters don't necessarily know that--not right away, sometimes never. They may not be ready to tell themselves they were misused by their government to fight for profit or for reasons other than freedom and justice. They just know they don't want to go out there when they know they will commit a massacre, or when they know their lives will be surely wasted, or when they know they will be subject to command rape.

By and large, people resisting in the military, the 10,000 deserters reported last year, the units refusing to commit massacres, the truck drivers refusing suicide missions, the female soldiers who died of dehydration (they too resisted), are not necessarily progressive political thinkers. They just got punched in the face, and fell flat on their backs. The antiwar movement needs to become that hand that helps them get up. They have to be on their feet before they can move forward. Before there can be a united front to end the occupation of Iraq, the antiwar movement should understand that the many struggles waged by servicemen and servicewomen against their mission and leadership are part of a painful process of realization that something has gone awfully wrong.

IN THIS book, I write about my first real act of resistance, which took place in Jordan right before the invasion. It was a matter simple enough to go unnoticed in the United States, but which I conducted with the secrecy of one who is engaged in treason. I asked a soldier in my squad to take a picture of me holding a sign that said: GIVE PEACE A CHANCE. When that picture was taken, I was not a politically aware person. I was informed enough to be against the war on political grounds, but had I gotten out of Iraq shortly after that picture was taken, I would have never considered becoming an activist, nor would I have ever believed that I could be one. That first act of resistance was followed by a slightly bolder one when I stood up for a soldier who was being abused by our leadership. At the time, I did not know that the same cruelty applied to that soldier would be applied to the people of Iraq once we got there, only with more force and on a much greater scale.

Small acts of resistance that respond to very specific situations in the battlefield or elsewhere in the military are directly tied to the larger injustice of war and occupation, but GI resisters may need help seeing that connection. In order to help them see the broader picture, we must meet them exactly where they are and not where we want them to be. That is why I think the work of Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) is so crucial in ending the occupation of Iraq. IVAW was founded by seven Iraq war veterans at the VFP convention in Boston, Massachusetts, in July of 2004. Our membership consists of active duty and reserve service members as well as of veterans who have served in the U.S. military since September 11, 2001.

The three stated goals of IVAW are the immediate and unconditional withdrawal of all occupying forces from Iraq, U.S. government reparations to the people of Iraq so they can rebuild their country on their own terms, and full benefits to all servicemen and servicewomen, and to all veterans. In order to reach our goals, we are dedicating ourselves to removing military support for the war. We are organizing active duty bases and guard and reserve armories, reaching out to veterans, and going into schools to teach the youth about war and military life so they can make informed decisions about joining the service.

The most ambitious project we have at this time is the organizing of the Winter Soldier Investigation: Iraq and Afghanistan. From March 13 to 16, 2008, we are bringing to Washington, D.C., more than one hundred U.S. veterans and civilians from Iraq and Afghanistan to testify about atrocities committed by our military in those countries. We hope not only to provide an honest picture of the awful reality of those two wars, so that people in the United States can finally see what their government is doing in their name, but also to organize the servicemen and servicewomen who may feel alone in their opposition to the occupation of Iraq.

With the larger peace movement and with the mentorship of our predecessors in Vietnam Veterans Against the War and VFP, we can help young servicemen and servicewomen channel their energy into a path of resistance that leads to justice. Their journey, and ours as we walk with them, is a long and winding one, but one we cannot afford to abandon. As with the writing of this memoir, the reasons why GIs embark on their different journeys of resistance may vary over time, and may have little to do with what we initially tell ourselves. But when we find our voices as a way to reclaim our love for humanity and our dedication to justice, there can be no punishment severe enough to keep us quiet. Speaking out becomes the moral fabric that keeps our existence together.