The roots of affirmative action lie in the struggle

The courts, the media and political leaders all downplay the real source of affirmative action: a rich history of struggle for equality and liberation, writes .

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION is in the news again after the closing arguments wrapped up early November in Boston federal court regarding the case of Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard — the lawsuit alleging that Harvard discriminates against Asian American applicants. The case is one of many suits since the late 1970s challenging affirmative action policies in college admissions.

Affirmative action policies are the product of struggles from below demanding measurable action to remedy a history of oppression — thus, their origins lie squarely in the Black freedom struggle.

For the left, defending affirmative action is necessary in responding to all instances of oppression, which is the precondition for building working-class unity. Calls to dismantle or dismiss affirmative action policies today are an affront aimed at diminishing the capacity to build solidarity and unity when our struggles need it most.

Like any reform, affirmative action has its limits — above all, it accepts the competition that is inherent to capitalism, whether over jobs, college admissions, access to housing and more. But it is a crucial advance in addressing the just demands of the oppressed.

The conservative lawyer behind the latest Harvard case, Edward Blum, is best known for his 2016 attempt at claiming “reverse racism” in Fisher v. University of Texas, an unsuccessful lawsuit attacking UT Austin for its affirmative action policies.

Now, Blum is alleging that Harvard employs racially and ethnically discriminatory undergraduate admissions policies designed to specifically discriminate against Asian American applicants by imposing quotas to achieve racial balancing.

While the SFFA v. Harvard case doesn’t raise any new legal challenges to affirmative action, opponents like Blum aim to transform public opinion during a period of deepening political polarization.

Currently, eight states limit or eliminate affirmative action in education — six of those states established limits through voter referendums. But the debate around affirmative action reaches beyond the attack on higher education.

For the last 40 years, the right has carried out state-by-state legal and political attacks against any measure directed toward ending discrimination in voting, health care, education, housing, employment, public accommodations, criminal justice and more. In the process, public debate has shifted further to the right.

This shift in the debate has added to the myths about affirmative action — including its characterization as “reverse racism,” that it benefits only Blacks at the expense of other oppressed groups, that it gives preferential treatment to minority students/workers over whites, and that it’s outdated and what we really need is affirmative action policies based on class, not race, gender or sexual orientation.

MAINSTREAM HISTORY traces the creation of affirmative action policies to the early 1960s during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations — starting with John F. Kennedy’s 1961 Executive Order 10925, which required government contractors to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed and that employees are treated during employment without regard to their race, creed, color or national origin.”

The 1964 Civil Rights Act, passed during the climax of the civil rights movement, aimed to eliminate discrimination and segregation based on “race, color, religion, sex or national origin” in voting, employment, education and public accommodations.

Finally, Johnson’s 1965 Executive Order 11246 extended the promise of the Civil Rights Act to employment in the federal government by providing “equal opportunity in federal employment for all qualified persons, to prohibit discrimination in employment because of race, creed, color or national origin, and to promote the full realization of equal employment opportunity through a positive, continuing program in each executive department and agency.”

While many of the current legal battles around affirmative action stem from challenges to the 11 titles and provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the historical origins of affirmative action are much richer when examined alongside struggles for emancipation.

Ten Historical Moments and Periods of Struggle that Affected Affirmative Action

1851: Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave and devoted abolitionist, delivered her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech to a white, mostly middle-class, suffragist women’s convention in Akron, Ohio, connecting the struggle for the abolition of slavery to the women’s movement to attain the right to vote by elevating the call for equality to one of liberation.

1860-1880: The Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution abolished slavery, which together freed more than 4 million slaves. But how to make emancipation a political and economic reality immediately became a question.

Freed slaves organized mass meetings, developed organizations and took up political action around these open questions, with an emphasis on the right to vote and the redistribution of the land, providing a picture of what reparations could look like after hundreds of years of slavery.

During the period known as Reconstruction after the war, questions of how Southern society should be organized were taken up by the federal government itself with a series of radical reforms to transition former slaves to freedmen.

W.E.B. DuBois explained the revolutionary character of these questions for both Black and white workers in the South and North and within the debates in the ruling class on the questions facing the future of U.S. society in his groundbreaking analysis Black Reconstruction:

The first fruit of the growing understanding between industrial expansion and abolition-democracy was the Freedmen’s Bureau. While industry in the North was dividing the labor movement and establishing a far more effective dictatorship of capital over labor than it had ever had before, it was compelled in the South to institute [a system of reforms] designedly and expressly for the protection of emancipated Negro labor. In the Freedmen’s Bureau, the United States started upon a dictatorship by which the landowner and the capitalist were to be openly and deliberately curbed and which directed its efforts in the interest of a Black and white labor class. If and when universal suffrage came to reinforce this point of view, an entirely different development of American industry and American civilization must ensue.

Under the protection of federal Reconstruction programs — and federal soldiers deployed in the conquered states of the Confederacy — Blacks were able to acquire land and negotiate tenancy contracts and raise money to purchase land and build schoolhouses. And they were able to participate in the political system for the first time, with Blacks elected to local offices, state legislatures and even the U.S. Senate.

But the Southern ruling class reorganized itself began to carry out an armed struggle against the Reconstruction regime, led by white supremacist organizations and militias such as the Ku Klux Klan.

Reconstruction came to an end in 1877 when the federal government agreed to withdraw its troops from the South. Those soldiers were soon put to work against the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

This connection was not a coincidence. Reconstruction had given strength to developing workers’ struggles in the North. The federal government’s actions in 1877 represented a reconsolidation of the U.S. ruling class, North and South, around a consensus for abandoning the democratic agenda of the Reconstruction process and uniting against the rising threat of the young labor movement.

In the South, the vacuum of power was filled with racist terror and corrupt state governments that quickly became all-white. But the inspiration and legacy of the Black struggle of this era would spill over to the labor struggles in the North at the turn of the 20th century, often led by immigrant women and Black workers themselves.

1868: Amid Reconstruction, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution granted citizenship and equal legal rights to former slaves, with the words: “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

1896: In the post-Reconstruction era, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in the Plessy v. Ferguson case that the 14th Amendment didn’t prohibit a “separate but equal” society, essentially delaying the promise and reach of the 14th Amendment by providing the justification for the segregationist policies that would persist throughout the Jim Crow era.

1934-1937: As the realities of the Great Depression set in, a new labor movement went into motion, leading to the formation of the mass industrial unions that the existing labor movement had refused to organize.

Socialists and anarchists were at the heart of these struggles — from the three great general strikes of 1934 to the tidal wave of sit-down strikes and labor victories that began with the 1936-37 Flint Sit-down Strike against General Motors.

Because the left played a central role, the new labor movement of the Great Depression was generally committed to not only winning increased economic rights, but also equal political and social rights for minorities.

1935: The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935 established collective bargaining and the National Labor Review Board. Employers found to be practicing discriminatory labor practices were required “to take such affirmative action including reinstatement of employees with or without back pay.”

Although the language of the NLRA didn’t directly raise race or national origin, these questions were central to the struggles of the rising labor movement that provided the mass pressure for winning New Deal legislation such as the NLRA.

New Deal policies weren’t enacted because of the benevolence of Franklin D. Roosevelt. They were the result of mass pressure from below, and the reforms of the New Deal represent important advances for the whole working class that we still celebrate today.

But on the issue of racism and equal rights, there were obvious failings and betrayals. While the National Recovery Act (NRA), passed in 1933, required nondiscriminatory hiring and an equal minimum wage for Blacks and whites on paper, in practice, NRA public works projects employed very few Blacks, and there had racist wage differentials. African Americans started calling the NRA the Negro Removal Act.

June 25, 1941: Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, titled “Prohibition of Discrimination in the Defense Industry.” This was a contradictory call to end employment discrimination in “industries engaged in defense production solely because of considerations of race, creed, color or national origin,” while rallying workers around “national unity.”

The order didn’t specifically use the term “affirmative action,” but it did outline a three-point program requiring institutions to “take special measures” to assure programs were administered without discrimination; obligating employers not to discriminate; and appointing a committee on “Fair Employment Practice” to “effectuate the provisions” of the executive order.

1945-1968: The legal changes and development of modern affirmative action policies can’t be separated from the civil rights movement, also known as the Second Reconstruction.

The movement began as a result of Black soldiers, who faced segregation according to the official policy of the supposedly integrated Army, returning from the Second World War to now face Jim Crow laws and racist terror in the South, as well as long-established racism in the North.

Langston Hughes wrote about the contradictions facing the Black soldier in his poem “Beaumont to Detroit: 1943”:

Looky here, America

What you done done —

Let things drift

Until the riots come.Now your policemen

Let your mobs run free.

I reckon you don’t care

Nothing about me.You tell me that hitler

Is a mighty bad man.

I guess he took lessons

From the ku klux klan.You tell me mussolini’s

Got an evil heart.

Well, it mus-a been in Beaumont

That he had his start —Cause everything that hitler

And mussolini do,

Negroes get the same

Treatment from you.You jim crowed me

Before hitler rose to power —

And you’re STILL jim crowing me

Right now, this very hour.Yet you say we’re fighting

For democracy.

Then why don’t democracy

Include me?I ask you this question

Cause I want to know

How long I got to fight

BOTH HITLER — AND JIM CROW.

1964-1975: The struggles of the late civil rights period and the years that followed were shaped by the gains and limitations of the civil rights movement. As in the 1930s, it was struggles from below that forced the pace of social reform policies.

By the mid- to late 1960s, the spirit of the civil rights movement had spread across the country, igniting the Black Power struggles as a further phase of the Black freedom struggle.

To take one example of how this era affected all of society, the Black Power movement led to a struggle by Black workers in the auto plants of Detroit and across the country, including wildcat strikes that were over both economic and anti-racist demands, and that pitted rank-and-file workers against both the powerful auto companies and the bureaucratized United Auto Workers union.

Thus, the May 1968 wildcat at Dodge Main was sparked by a situation in which only 2 percent of both foremen and union shop stewards were Black. The Dodge Main strike led to the formation of Revolutionary Union Movement organizations and finally the League of Revolutionary Black Workers founded in 1969.

In turn, the Black struggle provided a model for a mass antiwar movement against the U.S. war in Vietnam, as well as for other movements of the oppressed. The 1960s and 1970s saw organizations form to fight for women’s liberation, LGBT liberation, Red Power and more, with a tide of demonstrations and political action to demand change.

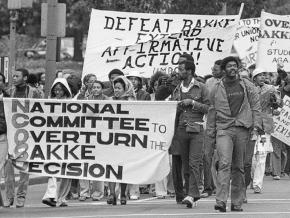

1978: The U.S. Supreme Court limited the reach of the 1964 Civil Rights Act in its 1978 decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke.

This decision was a clear setback for affirmative action. The justices ruled that Allan Bakke — a white male medical school applicant who claimed he was discriminated against when he was denied admissions at the University of California Davis — was a victim of “reverse racism” as a consequence of affirmative action policies.

But the majority decision also stated that race could still be one of many factors used by admissions in the effort to assure a diverse student body.

THE BAKKE case was the beginning of a series of challenges against affirmative action that continues to this day. In the historical context described above, the 1978 decision clearly moved the framing of the debate about inequality in the U.S. from a matter of civil rights for all to a case-by-case, state-by-state implementation of the rights of individuals.

Today, when a lawyer like Edward Blum tries to pit Asian-American students against African Americans with his Harvard suit and reconstitute myths like “reverse racism” to rehash the same legal arguments, we need to put forward the history of the struggle from below that won the past gains we defend today.

We can start by championing the struggle of first-generation students at elite universities who are calling for an end to affirmative action for the rich — in the form of legacy admissions that give preference to the children of alumni, who are likely to be disproportionately white and well to do.

We can also focus on changing the broader campus climate by participating in union battles on campus and campaigns of solidarity.

The roots of affirmative action lie in the struggles of the exploited and oppressed for equality and liberation. Because this has been obscured by the right’s offensive against affirmative action, the left needs to bring our history, our hopes and our vision of solidarity and liberation to the debate.