Why Wisconsin went for Trump

writes from Madison about the political and economic dynamics that set the stage for Trump's victory--and how things might have turned out differently.

DONALD TRUMP'S upset victory in the presidential election depended on "flipping" a number of "Rustbelt" states that went for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012--Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin.

On the surface, Wisconsin was a particular surprise. The Republicans hadn't won the state in a presidential election in more than 30 years, and Hillary Clinton was consistently ahead in the polls throughout the campaign.

In addition, Wisconsin workers have a recent history of militant mass struggle against the reactionary anti-labor agenda of the Republicans. Just over five years ago, union members, students and others demonstrated in their tens of thousands in the state capital of Madison.

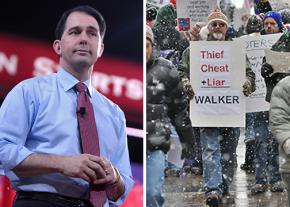

A three-week-long occupation of the Capitol building succeeded in temporarily blocking harsh anti-labor legislation being pushed through by newly elected Republican Gov. Scott Walker. Last year, Walker was a rival of Trump for the GOP presidential nomination, but his political career has been backed for years by the right-wing billionaire Koch brothers, whose reactionary agenda will now have an ally in the White House.

The uprising against Walker's agenda in Wisconsin was an inspiring example of how the right can be confronted. But its eventual defeat may have helped set the stage for this year's election result in one of the states that tipped the Electoral College, if not the popular vote, to Trump.

IN 2008, Obama won Wisconsin in a landslide, defeating the Republican candidate John McCain by almost 14 percentage points. Two years later, however, the state went Republican.

Widespread disappointment with Obama's first two years in office was part of the reason. At the state level, the Democrats, who controlled the governor's office and both houses of the legislature, had implemented austerity policies following the financial crisis of 2008.

With a much lower turnout than two years before, Walker easily beat the Democratic candidate for governor in 2010, Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, well known in his home city for cutting the budget and laying off city workers. Walker got 135,000 fewer votes in Wisconsin than McCain had, but Barrett got almost 680,000 less votes than Obama. Both houses of the state legislature switched from Democratic to Republican control.

During the campaign, Walker had been deliberately vague about his plans, playing up his image as a regular Wisconsinite who hadn't completed college in an effort to win votes from some sections of workers.

But within weeks of taking office at the start of 2011, Walker used a small deficit in the state budget as an excuse to launch an unprecedented attack on public-sector unions.

Walker made his announcement on a Friday afternoon. The following Monday, students from the University of Wisconsin--led by the Teaching Assistants' Association, the graduate student union--marched to the Capitol building in the center of downtown Madison.

Many signed up to speak at committee hearings on Walker's legislation, known as Act 10. The hearings continued into the early morning hours, and many people remained inside the building all night. The Capitol occupation had begun.

The next day, hundreds of teachers in Madison called in sick and joined the protests. Their numbers were soon swelled by thousands of other unionists from both the public and private sector. Even though Act 10 didn't apply to them, private-sector workers recognized that an injury to one was an injury to all.

Teachers from around the state joined the sick-out and converged on Madison. Tens of thousands of people clogged the Capitol building or joined marches and rallies outside.

In response to the pressure, Democratic senators decided to leave the building and deprive the Senate of a quorum so that Act 10 could not be passed. They soon departed for neighboring Illinois--so that Wisconsin state police couldn't find them and force them to return to vote in the Senate.

In the days that followed, the South Central Federation of Labor took the first steps to pursuing the logical next step. It set up a committee to inform member unions about how to conduct a general strike.

Whether or not a general strike was a realistic possibility, it was never pursued. The numbers of people at the Capitol kept growing, with hundreds sleeping in the building every night and as many as 150,000 people rallying outside for weekend demonstrations.

But union leaders soon began looking for ways to de-escalate the protests. Many teachers wanted to continue their sick-out indefinitely, but leaders of the state union narrowly won a vote to return to work. The unions proposed instead an electoral strategy of recalling Walker from office.

By March, Republicans in the Senate figured out how to separate parts of the legislation so that they could legally vote on it without the Democrats present. If the protests had been used to make the state ungovernable, the GOP may not have been able to get away with this. But instead, Democratic politicians and union leaders used this maneuver as an opportunity to wind the protests down and end the occupation.

SO ACT 10 passed--and its impact was as devastating as union members and their supporters feared.

It stripped public-sector unions of most of their collective bargaining rights; ended automatic dues collection; increased the amount that public workers paid for health and pension benefits; and required unions to recertify every single year, by winning the votes of a majority of the total bargaining unit, not just a majority of those voting.

By the time that Walker was eligible to be recalled the following year, the energy of the protests--which had pulled public opinion to the left--had dissipated. Activists gathered more than enough signatures to trigger a recall election, but it ended up being a replay of 2010, with the choice being between two versions of austerity. The result was that Walker slightly increased his margin of victory.

Five months later, with a much bigger turnout, Obama again comfortably won Wisconsin in the presidential election. His vote total was down slightly from 2008, but he still beat Mitt Romney by almost seven points.

But in 2014, Walker faced another uninspiring corporate Democrat in the gubernatorial election--Mary Burke, previously an executive with Trek Bicycle, a company owned by her family. Walker's vote total dropped from the recall election, but he still defeated Burke easily, by almost six percentage points.

Meanwhile, Walker's anti-union legislation was beginning to have profound effects. Before Act 10, more than half of the state's public-sector workers were unionized. As of last year, that number had fallen to just over one quarter.

Walker also used the fight over Act 10 to blame public-sector union members for cuts in education and public services. He accused government workers of being the "haves" in the state because they had better benefits than nonunionized workers.

The reality is that some public-sector employees are so poorly paid in Wisconsin that they are on food stamps. Others are forced to take second or third jobs.

After his reelection, Walker continued the attack on labor by pushing through a "right to work" law that severely weakening private-sector unions by overturning the practice of every worker covered by a labor contract contributing financially by paying union dues or labor fees.

Wisconsin, once a labor stronghold, has now dropped below the national average for union membership. Meanwhile, manufacturing jobs have continued to disappear, and economic inequality has continued to rise.

THIS WAS the background for this year's presidential election.

Wisconsin was wide open for a candidate who opposed corporate greed and growing inequality. Bernie Sanders ran on such a platform in the April Democratic primary and beat Clinton by over 13 percentage points, winning every county in the state except Milwaukee.

But once Sanders was out of the picture, Clinton--a former member of Walmart's board of directors and supporter of neoliberal trade deals like NAFTA--clearly needed to work hard to win the state.

Instead, she took it for granted. Clinton didn't visit the state during the general election campaign, and she stopped television advertising weeks before Election Day, confident that her lead in the polls was unbeatable.

But while Clinton did have a consistent polling lead, the danger signs for her are clear in retrospect.

First, her support was generally less enthusiastic. Second, there was a high number of undecided voters, and Clinton's business-as-usual campaign offered them little reason to make up their minds for her.

Finally, the Republican state government passed a voter ID law with the intent of making it more difficult for traditional Democratic Party supporters, including African-Americans and students, to vote. While the law was blocked by a federal judge before the election, it caused considerable confusion.

As one news report noted, "The biggest impact from these new barriers to voting comes not from people turned away from the polls, but from those discouraged from even showing up."

With an inspiring candidate, the barriers might have been overcome. But Hillary Clinton was not that candidate.

The result was that turnout in Wisconsin was the lowest in 20 years. Among undecided voters, exit polls showed that a clear majority broke for Trump in the last few days of the campaign.

The combination of a stronger turnout by the Republican base, lower turnout by the Democrats and some white workers switching to Trump in the misguided hope that he would reverse their economic decline led to Clinton's defeat in Wisconsin and the other Rustbelt states that provided Trump with his margin of victory in the electoral College.

In Wisconsin, Trump's vote total was barely higher than Romney's in 2012, but Clinton's was down almost 240,000 from Obama's. She lost the state by 26,000 votes.

In just Milwaukee County--which includes 70 percent of the state's Black population--turnout was down by almost 60,000 voters, and Clinton received 43,000 fewer votes than Obama.

Just as in much of the rest of the country, the numbers show that Clinton didn't lose because voters in general turned sharply to the right--although some did--but because she didn't give them a reason to turn out and vote.

"Milwaukee is tired," Cedric Fleming, an African-American barber who voted for Obama, but skipped this year's vote, told the New York Times after the election. "Both of them were terrible. They never do anything for us anyway."

Wisconsin workers have suffered major defeats over the past five years. It will take many years to rebuild the labor movement here. But the success of the Sanders campaign during the primaries showed there is still a huge audience for left-wing politics.

To be successful in the future, however, this sentiment will need to find a political expression outside the confines of a Democratic Party that betrayed it.